Affordable fuel cells could reduce the need for imported oil. However, solid oxide fuel cells currently don't fit the budget of most homeowners. The cost is tied to the internal temperature of the cell, around 1000 degrees Celsius. This temperature means the cell must be built using very durable, very expensive ceramics. Lower temperatures mean the cells could be built from stainless steel and other less expensive materials. The trick to dropping the temperature, and thus the cost, is the membrane or solid electrolyte that quickly passes oxygen from one side of the cell to the other.

In this study, the team investigated why some materials are better than others at passing oxygen along. "We could take an Edisonian approach—trying 10,000 materials, but it would be expensive, and we'd be here forever," said Dr. Ram Devanathan, a materials scientist at PNNL. "So, we are using all of the tools we have in EMSL—experimental, computational, and theoretical—to look into the materials."

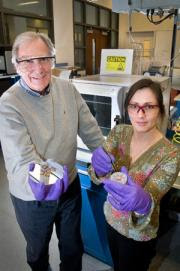

Using oxygen-plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy, the researchers grew scandia-stabilized zirconia films on sapphire substrates. The films were examined using x-ray diffraction, electron spectroscopy, and microscopy.

However, experimental data alone was not enough, Devanathan explained. Imagine taking photos at the beginning and end of a raucous party. The photos, like the experiments, show you where you began and where you ended. However, theory shows what happened and why. Theory also allows predictions about what will happen next and what would happen under different circumstances.

Using oxygen-plasma-assisted molecular beam epitaxy, the researchers grew scandia-stabilized zirconia films on sapphire substrates. The films were examined using x-ray diffraction, electron spectroscopy, and microscopy.

However, experimental data alone was not enough, Devanathan explained. Imagine taking photos at the beginning and end of a raucous party. The photos, like the experiments, show you where you began and where you ended. However, theory shows what happened and why. Theory also allows predictions about what will happen next and what would happen under different circumstances.

So, the team applied theoretical calculations and models to the experimental data. They determined that the nanoscale, nanosecond interactions occurring in the scandia-doped cubic film conducted oxygen faster than the yttrium doping in current electrolytes.

This study provides a fundamental understanding of how ions move in scandia-doped zirconia, and shows the material is very stable. "Our integrated approach takes the science to the next level," said Dr. Theva Thevuthasan, who worked on the project and currently oversees the deposition and microfabrication capability at EMSL.

The scientists are using resources at EMSL and PNNL to provide a more detailed understanding of the atomic interactions in another promising material for fuel cells: nano layers of zirconia and ceria.

This study provides a fundamental understanding of how ions move in scandia-doped zirconia, and shows the material is very stable. "Our integrated approach takes the science to the next level," said Dr. Theva Thevuthasan, who worked on the project and currently oversees the deposition and microfabrication capability at EMSL.

The scientists are using resources at EMSL and PNNL to provide a more detailed understanding of the atomic interactions in another promising material for fuel cells: nano layers of zirconia and ceria.

Oxygen (red spheres) migrates from one vacancy to another inside the scandia-doped cubic zirconia. The cations the oxygen must brush past are marked by the letter E

Nombre: Franklin J. Quintero C.

Asignatura: CRF

Dirección: http://www.physorg.com/news191576465.html

Ver Blog: http://franklinqcrf2.blogspot.com/